A Pilgrimage to Jerusalem (the song) - 1916-2016

To honour the 100 year anniversary of Jerusalem, Britain’s unofficial national anthem, in 2016 I created a 125 mile ‘Pilgrimage to Jerusalem (the song)’ from London to Sussex.

This was a journey on foot made with: Kitty Rice, James Keay, India Windor-Clive, Mathilda Wnek, Guy Hayward, Georgie Norfolk, Merlin Sheldrake, Cosmo Sheldrake (each in parts)…

Supported by:

The Blake Society (Honouring and Celebrating the work of William Blake)

Millican Backpacks (Making great backpacks in Britain)

Alastair Sawdays (Curators of accommodation in special places)

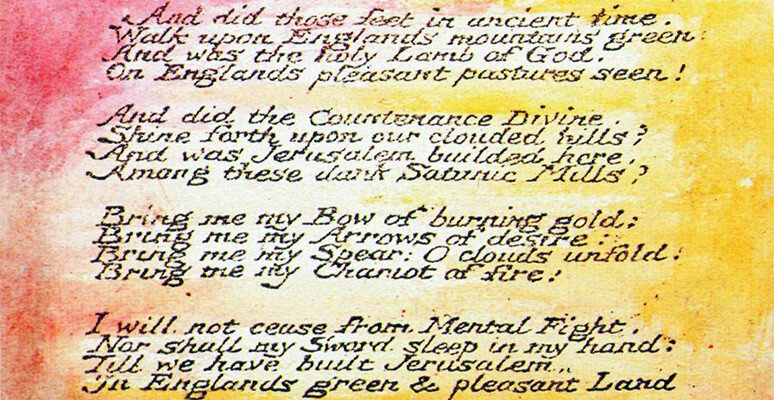

In the deepening dark of 2016, with a bunch of friends I made a pilgrimage from central London to coastal Sussex, to honour the 100 year anniversary of the song ‘Jerusalem’ – “And Did Those Feet in Ancient Times…”.

This song is the fruit of two people – William Blake, visionary poet and artist, and Hubert Parry, composer and director of the Royal College of Music. In 1804, Blake wrote the poem as part of his epic ‘Milton’. And in 1916, Parry set this poem to a rousing melody, designed to be sung by large groups of people.

William Blake

Hubert Parry